Ruixue Jia on the influence of administrative power in Chinese academia on researchers' publication activity, their selection of co-authors, and the topics they are writing about.

Description

It has been well recognized that power distribution plays an important role in economic development. In my research field, political economy, an influential literature emphasizes that political power distribution affects resource allocation, economic production, and consequently the fortunes of a country or a nation (e.g., North 1990, Acemoglu and Robinson 2012 among many others). In contrast, researchers have paid relatively less attention to the impact of power in academia, perhaps believing that in this context, resource allocation should be driven primarily by academic merit. In power-oriented societies, however, academia may not be immune to the influence of power. Analogous to how political power affects economic production, administrative power in academia influences scientific production. This is the point my coauthors and I illustrate in the case of Chinese academia (Jia, Nie and Xiao 2019).

We examined the relationship between administrative power – specifically, becoming a dean of a school – and publications in Chinese academia. We found that scholars published more after becoming a dean. Considering that deanship was associated with a large amount of administrative work, this finding may appear surprising. We then looked into various reasons to see what drives the increase in publications. Overall, the data fits better with the interpretation that administrative power matters for resource allocation in this context. As a result, scholars have incentives to cater to power by becoming co-authors with the dean, even though sometimes the dean may not be the expert on their own research topic.

We are not the first one to realize these issues in Chinese academia. On the one hand, China has become the world’s second-largest producer of research articles behind only the United States. On the other hand, it faces serious difficulties in improving research quality and efficiency, often attributable to its top-down administrative system (Xie, Zhang and Lai, 2014) and factors other than research ability, such as connections. Fisman et al., (2018) show that hometown ties with the selection committee members affect who becomes a fellow of Chinese Academies of Sciences and Engineering. Two leading scientists, Yigong Shi and Yi Rao, published an article in Science, stating that: “to obtain major grants in China, it is an open secret that doing good research is not as important as schmoozing with powerful bureaucrats and their favorite experts” (Shi and Rao, 2010). To be sure, what they pointed out is also relevant in other countries, but seems particularly salient in this context.

Below, we introduce our data, give an overview of the four takeaways of our study, and discuss two implications.

Our Data

Since all of us are economists, we focussed on our own field. We constructed a unique 1990–2009 dataset of the publication and biographical information of the deans of major research schools, departments, and institutions of economics. We considered publications in Chinese journals. Since the turnaround time of Chinese journals is typically shorter than one year, it is straightforward to define the time relative to gaining administrative power. We simply examined the publication records of these deans year by year, before and after their appointment.

Takeaway 1: Power Increases Productivity.

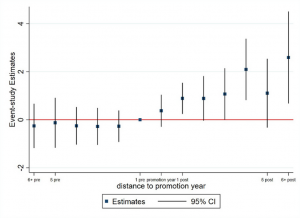

Deanship increases an individual’s publication by 0.7 articles per year, which is large (about 37% of the mean number of annual publications). Figure 1 illustrates the year-by-year patterns before and after an individual becomes a dean. As shown, there is a notable increase in the number of publications post-deanship. In contrast, there is not much improvement in productivity in the years before one becomes a dean, suggesting that it is not improved productivity itself that leads to power.

Figure 1: Number of publications before and after becoming a dean.

Takeaway 2: It is a Specific Type of Coauthorship.

The increased publications stem from work coauthored with other researchers within the same university. We examine single-authored and co-authored papers separately and find that the increase stems from the latter. For the co-authored papers, we further use the affiliation of authors to define local collaboration events (with scholars in the same university) and non-local collaboration events (with scholars beyond the university). We find that the increased publications stem from work co-authored with other researchers within the same university. In contrast, no similar change is observable for collaboration with researchers outside the dean’s university. This finding is consistent with the fact that the influence of power is usually restricted within a university.

Takeaway 3: Power also Changes Publication Topics.

The topics of the increased publications are more likely to deviate from the deans’ research area prior to becoming deans. We use the articles published more than five years pre-deanship as the benchmark to define one’s research area and examine cognitive similarity in publications year by year. We find a pattern of topic changes after one becomes a dean: The topics of the post-dean publications are more likely to deviate from one’s earlier research. Thus, deanship does not only affect the quantity but also the topics of publications: Once gaining deanship, one becomes more likely to publish research on topics they were less familiar with.

Takeaway 4: The Power Effect is not a Constant.

The power effect varies greatly by university, by journal, and by individuals. First, using information on university ranks, we find that the power effect is much lesser/weaker in elite universities (known as Project-985 universities, a group of 39 public universities designated as the national elite tier in May 1998). Second, the impact of power matters less for the Top-4 journals in this context. Finally, the power effect is also less important for individuals who were already very productive before becoming a dean. In other words, it is the less productivity scholars that benefit more from obtaining administrative power.

Implications

There are at least two important implications one can draw from these findings:

First, these patterns suggest that power creates distortion in knowledge production. In principle, one can consider three interpretations for why power matters. One can assume that those with an increasing productivity trend are more likely to be selected for promotion to dean. They get more publications thanks to their ability. We call this the “ability effect”, which contradicts the figure above. One can also conjecture that the possible influence of a dean’s reputation may facilitate publication. Other scholars may believe that including them as authors will increase their chances of publication. If this “reputation effect” were important, we should expect to see a similar increase in collaboration beyond the dean’s university, which is not the case. Instead, our findings appear most consistent with an “resource effect” interpretation, where administrative power affects resource allocation, which motivates scholars within the same university to collaborate with the dean. Since scholars face a choice of spending their time doing research and cultivating a good relationship with the dean, our findings also imply that scholars’ effort decision can be distorted, as well expressed by the quote of Shi and Yao mentioned above.

Second, power can be constrained by institutions. In particular, we find that the power effect in top Chinese universities is weaker than in non-top universities. Multiple channels can account for this pattern. For instance, there is more competition among peers in elite universities, which can constrain the abuse of power. Another factor is that faculty members tend to have fewer outside options in non-elite institutions, and thus have stronger incentive to cater to the interest of the leader. Therefore, our findings deliver a hopeful message: Power can be constrained by appropriate institutions. The current problems we pointed out in Chinese academia are certainly remediable if there can be reforms to restrict administrative power and grant scholars more autonomy.

Relevance to Other Fields and Countries

Our results are based on a specific field in social sciences in China. The phenomenon that administrative power influences scientific production is not unique to China. Using data from both European and U.S. universities, Aghion et al. (2009) show that academic autonomy and competition are important determinants of scholarly output. We hope that there can be more comparative studies documenting how administrative power shapes knowledge production across fields and countries. Our findings are also likely to be relevant for natural sciences. We plan to study administrative power matters for important long-run outcomes like innovation in our future work.