The COVID-19 is prompting many museums to reconsider how they communicate their research to the public, says our editor Rebecca Kahn

Introduction

The current COVID-19 crisis has prompted hand-wringing and self-reflection among some museum professionals. What, they are asking, is the point of a museum that remains closed to the public? How can museums remain relevant if people can’t visit them? Can exhibitions, which take years to plan and execute, be transferred to the digital realm, in order to keep museums open virtually? This crisis has raised a raft of questions for museums, some of which pertain to their relevance – if they have to remain shut – and others which address how best museums might evolve to reflect the current situation, and what their role might be post-COVID-19. Who can a museum serve, if their only instance is an online version? These are crucial questions, and all of them fall within the remit of a museum’s role in a community. And if anything, the current crisis has forced museums to consider questions that have been emergent for some time (Cameron, 2015) and which, if they are able to respond to them, might not only help them weather the storm, but emerge stronger, and more resilient.

The current COVID-19 crisis has prompted hand-wringing and self-reflection among some museum professionals. What, they are asking, is the point of a museum that remains closed to the public? How can museums remain relevant if people can’t visit them? Can exhibitions, which take years to plan and execute, be transferred to the digital realm, in order to keep museums open virtually? This crisis has raised a raft of questions for museums, some of which pertain to their relevance – if they have to remain shut – and others which address how best museums might evolve to reflect the current situation, and what their role might be post-COVID-19. Who can a museum serve, if their only instance is an online version? These are crucial questions, and all of them fall within the remit of a museum’s role in a community. And if anything, the current crisis has forced museums to consider questions that have been emergent for some time (Cameron, 2015) and which, if they are able to respond to them, might not only help them weather the storm, but emerge stronger, and more resilient.

As museum professionals and museum scholars begin to engage more deeply with the realities of our new museological order, these early forays into what a digital museum could be also risk perpetuating deeper misconceptions about what the purpose of a museum is, and reinforcing the incorrect assumption that there is a zero-sum game playing out between ‘virtual’ and ‘real’ exhibitions in the first place. At the heart of this tension lies the need to find ways to highlight and bridge two of the most important roles museums have: as sources and spaces for scholarly communication (in other words, museums as knowledge repositories) and as places for science communication (museums as sources of informative entertainment). Both of these roles have, until now, been situated in the physical space of the museum. However, in thinking through an evolution which is digital and hybrid, COVID-19 offers the potential for museums to reveal their inner workings, and potentially share much more with their virtual visitors.

Museums as sources of science communication

The museum as a science communicator is probably the one that most people are familiar with. In this formulation, museums can be seen as places of leisure and entertainment. They are places we might go to when we’re in a new city, to try and help us get a sense of the place and its history. Or somewhere we go on a rainy weekend, when there are dinosaur-obsessed kids to entertain. We might visit one of the many blockbuster exhibitions of painted masterpieces, or hoards of ancient artefacts. Perhaps we first went to a museum as school children, to see certain exhibitions and special collections which related to a syllabus. Sure, learning something is an aspect to these visits. Museum visits can be transformational, providing visitors with up-close and personal experiences of seeing specimens or artefacts, and are a significant aspect of the science communication role of the museum. But the pedagogical part of the experience is balanced by the context in which it takes place. Museums become spaces we interact with via galleries, touch-screen kiosks, cafes, restaurants and gift shops. Museums take these different points of contact seriously (Koszary, 2018) audience engagement is considered to be a crucial component of a museum’s work, and visitor experience is a growing concern for curatorial teams, who focus on making museums welcoming, inclusive and easy to navigate. It is also a growing area of research for museum scholars.

Researchers who study the ways in which visitors engage with museums (Pekarik, Doering & Karns 1999; Kirchberg & Tröndle, 2012) categorise visitor experiences in terms of how the viewer responds cognitively to an object and it’s placement within a gallery. In their formulation, a museum is capable of creating multiple moments where it would be possible for scientific communication to take place. However, these categories are, by definition, highly situated, and assume a physical proximity between viewer and objects. They also, crucially, leave little room for dialogue. In the last twenty years, the traditional role of the museum as an omniscient institutional voice, which dictates significance, and leaves little leeway for interpretation or response from the visitor has also been rejected (Macdonald, 2016; Weil, 2007; Witcomb, 2003). But how to mitigate these experiences, and in particular via digital technologies, when it is almost impossible to know who might be logging on to a museum’s digital offerings, and what their cultural, educational or social background is, is an ongoing discussion among museum professionals, and one which is extremely complex.

Museums as knowledge repositories

Museums’ role as a place for educating and entertaining those who walk through the doors is just the tip of the iceberg, when it comes to considering what a museum actually does. International Council of Museums (ICOM) is the global body, affiliated with UNESCO, which acts as an umbrella organisation for museums all around the world. They currently define museums as institutions which are: ‘…participatory and transparent, and work in active partnership with and for diverse communities to collect, preserve, research, interpret, exhibit, and enhance understandings of the world…’ The activities described by ICOM include fighting the illicit traffic in cultural goods, and promoting risk management and emergency preparedness to protect world cultural heritage in the event of natural or man-made disasters. But for the purposes of this discussion, it is the ‘research and interpret’ aspects of a museum’s activities, or, as previously described, the museum as knowledge repository, that provides an intriguing possibility for a revisioning of what museums could be in these times of COVID-19 restrictions.

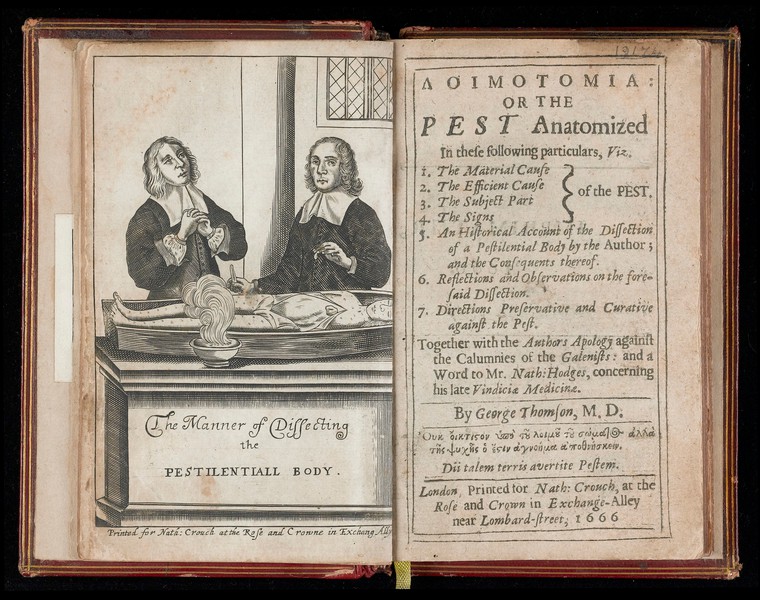

Museums play a crucial role in the development of knowledge, which is closely related to their role as science communicators, but this role manifests in a very different, less publicly-engaged way. The first versions of museums were the Wunderkammer or cabinets of curiosities, which were huge, sometimes haphazard collections of natural history specimens, artefacts and curiosities, amassed by princes, dukes and other men of stature. These collections, and the institutions they evolved into, have provided the source materials for the research which has helped us learn more about our world. One of the key functions of museums is to act as repositories of cultural memory (Morgan & Macdonald, 2018) gathering up material objects and information to guard against its anticipated loss. In practice, this means that all over the world, in specially climate controlled environments, sit boxes and shelves full of stone tools, shells, bits of grass, animal skins, tree bark, bone, textiles, porcelain, glass and paper, as well as jars and bottles full of preserved animal and insect specimens. But how many of these things can one museum possibly need? Why bother keeping them, if nobody except a few curators and preservation experts will ever look at them? And particularly now, when nobody can access them? One reason why these collections matter is that museums are much more than places where the public can spend a few hours wandering through an exhibition (stopping halfway for a sustaining coffee and cake). Museums are vital sites for research, which has always gone on behind the scenes in these institutions. Just as books form the basis of scholarly research in libraries, so museum collections, and the documentation that accompanies them, is the basis for the research activities of museum professionals and other scholars. The Natural History Museum in London is home to the Darwin collections, which include the specimens of birds, corals and mammals which formed the basis of his theories on the evolution of species. The Münzkabinett of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin is one of the most significant numismatic collections in the world, which provides scholars with material for studying the early history of science and metallurgy, as well as the social and economic history of societies from Asia Minor in the 7th century BCE to the significance of coins and medals from the 21st century. The National Museum of African American History and Culture, which is one of the Smithsonian Institution’s twenty museums and research institutes, holds materials which have allowed researchers to highlight the role of African American soldiers in World War I and the impact this had on American society. All three of these institutions, which are currently closed, have made these, and other collections and exhibitions available online, with varying degrees of granularity, for the duration of the crisis.

Unlike a record of a book in a library, which will tell a user where the book is, but not provide access to the content, museums store the knowledge about an object in its record. All the research that is conducted on an object will be recorded by the curators, and it is constantly updated as more research is done. Often, this information cross-references other objects, which share a provenance, or are connected to individuals or periods. However, very little of this information makes it to the broader public. There are several reasons for this, the most notable being that, in most museums, only about 10% of the holdings ever go on display. So very little content is visible. Secondly, records and objects are usually kept separate from each other. Objects live in stores, often offsite. Records exist in printed catalogues, or databases, and reconciling the two can be difficult, even for curators (Blagoyev, Felten, Kahn, 2018). The physical, disciplinary and logistical walls, which keep knowledge and objects apart in museums, can also be seen as being replicated in the digital space. Digital gallery views rarely include data about the object, other than a title, and perhaps a creation date. This is ironic, since there is no limit to the ‘space’ a digital object can take up, and embedding information in a 2 or 3D object is no longer technically complex. Although many museums strive towards creating ‘museums without walls’ the potential of a truly distributed, international museum ‘collection of collections’ promised by the web remains largely unrealised (Chan, 2019). However, a narrowing of the gap between the museum-as-science-communicator, and the museum-as-knowledge-repository might provide the blueprint for making what is available richer, and allowing visitors to look deeper into collection and object documentation.

Exploiting Affordances

Since museums were forced to close, some institutions have taken to Twitter, which is an unusually rich space for museum discourse (curators are good at fitting a lot into a few words) to curate crowdsourced views of institutions and heritage sites using the hashtag #museumsunlocked. Others are directing potential visitors to their Google Arts and Culture instances, where selected parts of their collections can be explored, often with extended notes and information. These initial attempts to provide access are admirable, in particular because they offer a way for non-local audiences to access collections that they might never have been able to see in the past, and may no longer have the opportunity to in an uncertain future. But much of this feels like ‘business as usual, just on the internet’. This might be an effective way of weathering the immediate storm, but it is clear is that simply creating a website or hosting a social media presence which allows for a one dimensional transfer of knowledge from the institution to the audience is no longer considered a sufficient proxy for digital engagement.

Crisis as opportunity

The reality is that there is also an opportunity to be seen in the current crisis, if we take a slightly longer view. There has been pressure for museums to make critical changes for some time, and, while alarming, COVID-19 might be just the impetus needed to kickstart those changes. If museums take the “let’s sit this out, and see what happens approach” they are far less likely to emerge with evolved, healthy and flexible identities that will be needed to continue their roles as preservers of knowledge and transmitters of communication in the post-epidemic world.

Online or digital exhibitions, which replicate, extend and supplement physical collections are gradually becoming more commonplace, but among museum professionals, there is a general lack of consensus about what a digital or online exhibition might be, and, until the COVID-19 crisis, about whether they are a valuable strategic strategic option for museums (Hartig, 2019). Much of the disagreement has arisen because online exhibitions initially developed as supplements to physical exhibitions, in the same way that galleries, in many museums, were, for a long time, considered to be the central display spaces, supplemented by gift shops, kiosks and cafes. Galleries (and their digital surrogates) are often seen as being overly editorial, with too much text, flat images, and little choice provided to the viewer as to how to navigate them (Kahn, 2017). Digital offerings, the emerging consensus seems to be, should not rest at being digital copies of what exists in the gallery. The key is to make use of the affordances of the medium, which includes autonomy, multi-layered multimedia, and linked content. Creating materials that are designed with digital in mind, rather than as an afterthought, would allow museums to consider how they might be able to act as both knowledge repositories, and science communicators to the entirely new audiences that have been, and will continue to turn to them as the crisis keeps people at home, and looking at their screens. Erin Blasco, who runs social media for the Smithsonian, has argued that, in the short term, museums should forget about physical exhibitions, which may or may not ever open, but rather consider telling their stories using materials that are already freely available online, such as in their archives, in online repositories, and even in other institutions. This approach will allow museums to become a different kind of science communicator, using open science materials already available.

Very, very big data

At the research level, in a larger, more complex scale, several institutions have already begun to experiment with the semantic web, and linked data as a way of connecting their databases (which may contain several million records) and creating multi-layered and multimedia collections, which focus as much on the records as the objects. This is no small task, and to date, much of this work is in the early stages of technical development and proof of concept work. This infrastructure-building is a huge undertaking, and one which can be difficult to justify to directors and museum trustees who might be concerned with immediate institutional reputation management. However, in the long term, it promises the potential for building robust knowledge transfer and communication tools, which would enable museums to continue communicating with their audiences and each other, despite the risks of future crises such as COVID-19.

Creating context

While online presences can deliver an ever-increasing array of interactive features for visitors to access images, it is also imperative to consider the interpretative, and historical context provided by museums and the curators who put together exhibitions. London’s Science Museum Curator, Suzanne Keene, has argued that web interfaces, particularly with museums, risk making knowledge more important than the collections themselves: ‘People will be able, so to speak, to help themselves to the information that the collections embody without mediation or interpretation’ (Reading, 2003). This anxiety, however, can be seen to highlight the need for museums in the light of a potential COVID-19-shaped future. Many people are struggling to make sense of the world, and museums are perfectly placed to help us do so, through their role as science communicators, and as collectors of our knowledge and culture. These roles, translated into digital content, need not emulate what can be done in a gallery. As one museum professional put it ‘a website doesn’t have walls, a gallery doesn’t have tabs’. Understood from this perspective, the potential offered by digital to provide rich, layered museum content, which fulfills the science communication role of a museum, and exploits their position as knowledge repositories is extremely exciting. The reality, however, is that creating, managing and hosting this content is not easy, fast or cheap. And as many museum professionals know (Perrin, 2016), a digital project can be fast, easy or cheap, but never all three. However, museums are very good at taking their time. Many of them have been collecting stuff for hundreds of years.

Dear Rebecca Khahn:

I’d like to ask your permission to have your article translated into Chinese language and introduce to Chinese readers worldwide.

I am the former Managing Editor for Chinese Cultural Relics, the official English translation of the Chinese Journal Wenwu. I am also the current Research Associate in History of Arts and Architecture of Department of History of Arts and Architecture at University of Pittsburgh.

I wish you healthy and safe during this pandemic.